Morcar and Edwin, Saxon Earls

Morcar and Edwin, Saxon Earls

The Northern Earls were prominent before the Battle of Hastings.

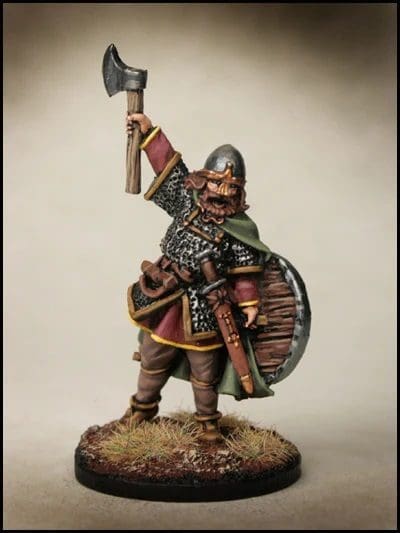

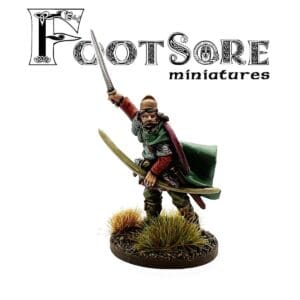

Pack contains two white metal figures and 25mm bases.

Miniatures supplied unpainted and may need some assembly.

Examples painted by Sascha Herm.

Morcar, Earl of Northumbria (c.1040–c.1090)

Morcar was from the Mercian nobility, grandson of Leofric and his wife ‘Lady Godiva’, and son of Ælfric, earl of East Anglia. The family was in rivalry with the Godwines. In 1065, Morcar and his brother Edwin joined a rebellion in Northumbria against Harald Godwinson’s brother Tostig, and Morcar replaced him as earl of Northumbria.

When Tostig returned with Harald Hardrada in 1066, Edwin and Morcar gave battle but were defeated at Fulford, near York. Harold retrieved the situation by killing Tostig and Harald Hardrada at Stamford Bridge, but Morcar and Edwin did not march south with him to Hastings, possibly because their forces were shattered. On Harald’s death, the brothers tried to lead a resistance, failed, and submitted to William. In 1068, they rebelled and were again obliged to submit. After a further unsuccessful revolt in 1071, Morcar took refuge in the Isle of Ely, surrendered, and was imprisoned in Normandy. He was alive at the Conqueror’s death in 1087, but Rufus returned him to prison and no more was heard of him. His elder brother Edwin was killed by his own men in 1071.

Edwin, Earl of Mercia (died 1071)

Edwin became Earl of Mercia in 1062 after his father and grandfather. He and his younger brother Morcar, who was the Earl of Northumbria, played a key role in Harald Hardrada’s failed campaign to take England in 1066. They opposed him at the Battle of Fulford Gate on the 20th September (which they lost) and the Battle of Stamford Bridge five days later which gave King Harald Godwinson, their brother-in-law, victory over King Harald Hardrada of Norway.

Sadly for King Harald, the two brothers also played a key role in the Battle of Hastings by taking a very slow journey south and not turning up until it was all over. Florence of Worcester commented that they ‘withdrew’. On one hand, they did have to march rather a long way having just fought two battles in a very short space of time, but on the other hand, rather than share the loot after Stamford Bridge as was the custom of the time, King Harald had it all collected together in York. He appeared to have every intention of keeping it for himself, which may have left the two earls feeling somewhat peeved.

Evidence of Edwin’s failure to take part in the Battle of Hastings is reflected in the fact that he still owned property at the time of the Domesday Book.

It is an indicator of William the Conqueror’s desire for peace within his new kingdom that Edwin not only retained his land, but also his title. Following Hastings, Edwin and Morcar supported Edgar the Atheling in his claim to the throne. William had to chase them around the southeast for two months before they finally submitted at Berkhamstead. In 1067 Edwin was one of the hostages who accompanied William back to Normandy.

Obviously, things didn’t pan out to Edwin and Morcar’s liking, because they rebelled against William in 1068, and again in 1071. The Orderic Vitalis claims that one of Edwin’s gripes was that William had promised Edwin one of his own daughters in marriage, but appears to have had second thoughts about having Edwin for a son-in-law.

The 1068, rebellion saw William building castles and stamping his authority on the land. The Earls submitted once again to William and he graciously welcomed them back into the fold. In 1069, William appointed Robert de Comines to the job of Earl of Northumberland. Understandably Edwin’s brother Morcar was a little disgruntled by this turn of events, and the North rose up against William. In fact, all kinds of rebellions against Norman rule sprang up like forest fires in the first years of William’s reign. It is perhaps not surprising that William’s avowed intent to be a good lord to his new Saxon subjects eroded.

It was during Hereward the Wake’s rebellion in East Anglia in 1071 that Edwin was betrayed to the Normans by his own retinue and killed.

Edwin’s lands extended north from Gloucester up into modern West Yorkshire and beyond. His territory also included Craven. Following Edwin’s death, the lands were broken up. Robert de Romilly was given the lands in Craven.

$8.50

In stock

SKU: FSM 03LSX303

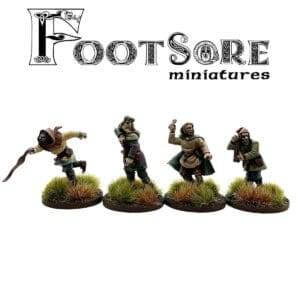

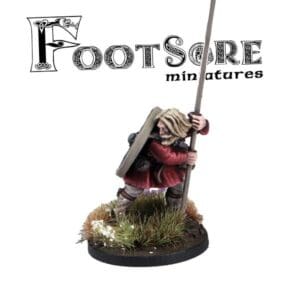

Related products

-

Æthelstan

$7.50Add to WishlistAdd to Wishlist -

Late Saxon Slingers

$10.50Add to WishlistAdd to Wishlist -

Late Saxon Fyrd Banner Bearer

$5.75Add to WishlistAdd to Wishlist -

Hereward the Wake

$4.50Add to WishlistAdd to Wishlist -

Late Saxon Lord

$4.50Add to WishlistAdd to Wishlist -

Harald Godwinsons’s Standard Bearer

$4.50Add to WishlistAdd to Wishlist -

Alfred the Great

$7.50Add to WishlistAdd to Wishlist -

Late Saxon/Anglo Danish Lord

$7.50Add to WishlistAdd to Wishlist